Seamless

Mai Okimoto’s “Where Sidewalks Never End” — a piece that takes you on a peaceful walk through São Paulo’s República neighbourhood. Reading it somehow led me to wander inside an Ottoman miniature, where spaces blur and even time flows differently.

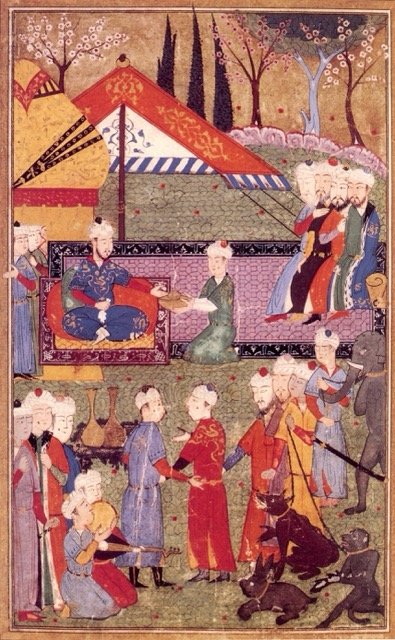

Miniature from a copy of Ahmadi's İskender-nāme, middle of the 15th century, written and painted in Edirne, now in Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venezia

I was actually planning to write a short Instagram post for this Sunday, but the more I wrote, the longer it got, so it turned into a blog post instead.

This Sunday’s read is “Where Sidewalks Never End” by Mai Okimoto, along with a little reflection of my own. A piece that somehow led me to wander inside an Ottoman miniature.

Link to Mai’s piece: Where Sidewalks Never End

Recently, I read Mai’s piece, which is one of the four pieces in their recent “The Sidewalk Issue”, and it takes you on a peaceful journey through São Paulo’s República neighbourhood. A place I’ve never been to, yet by the end, it feels as though I’ve walked its streets myself. Mai focuses on the network of passages and sidewalks that weave through the area. As the title suggests, the sidewalks seem endless, extending seamlessly from one space to another.

I enjoyed the text for two main reasons. One connected to the discourse and the other more personal.

First, the discourse part. I love how these endless sidewalks create a kind of border within the neighbourhood. (I deliberately say border, not boundary. In architectural discourse, this distinction matters: a boundary defines a strict line, separating spaces completely, whereas a border is thicker, softer. A threshold where two sides meet, overlap, and create a space of transition.) In República, this network of passages embodies this idea of the border beautifully.

The blurred condition between public and private, outside and inside, together with the endless sidewalks and the photographs in the piece, evoke a sense of continuous experience. A seamless movement that carries you through the text and through the neighbourhood itself.

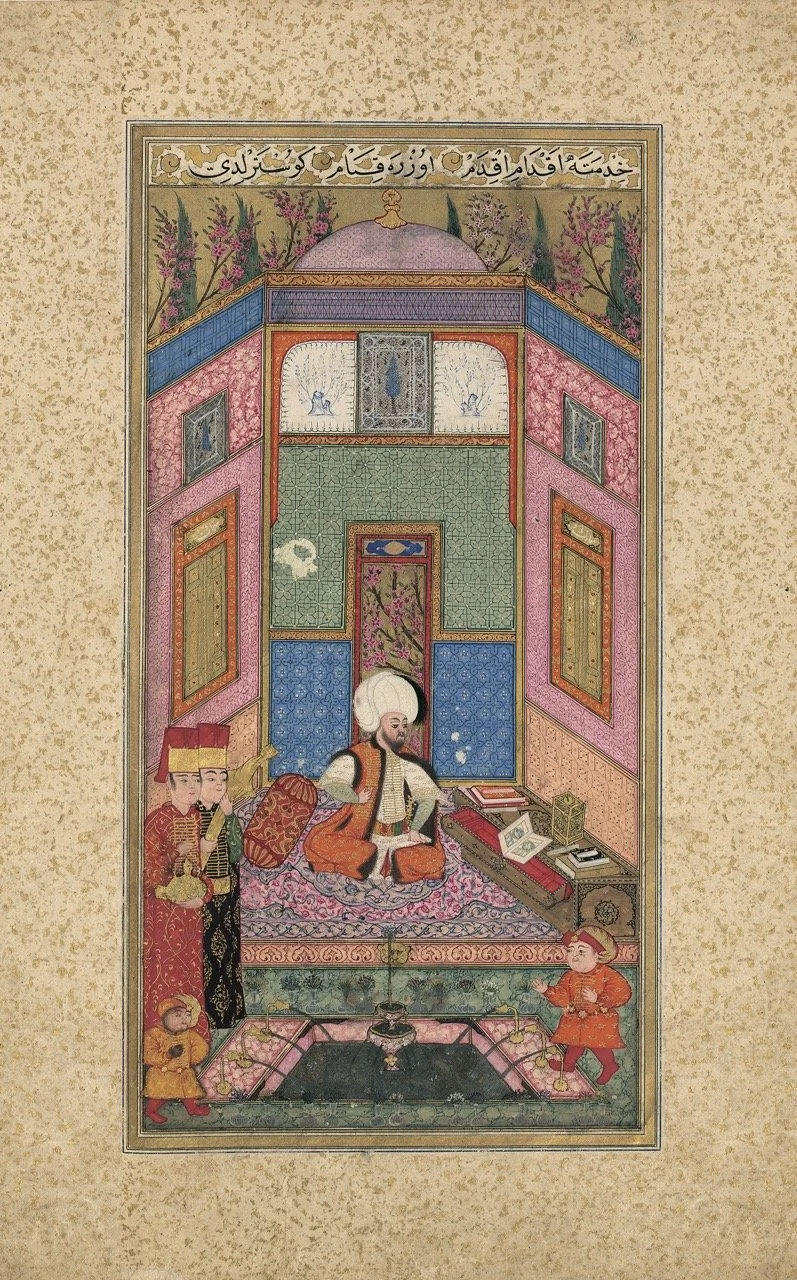

Sultan Murad III in The Book of Felicity (1582)

Now, for the second reason I enjoyed the piece. And this one’s closer to me. Reading Mai’s piece made me feel as if I was wandering inside an Ottoman miniature. A topic I actually want to write about in the coming weeks.

In Ottoman miniatures, spaces are not defined strictly by walls, doors, or gates; instead, they’re shaped by the flows of people. Again, it’s about borders and that blurred condition. Actually, it is not just space that behaves differently, but time as well. There is no strict linearly in time in miniatures. A single depiction can hold several moments at once. A king might be shown welcoming visitors in his palace while also riding his horse into battle in the very same miniature depiction.

Ottoman miniatures privilege the flow of people and experience over enclosure, much like the covered passages of São Paulo’s República neighbourhood.

Are the Parks an ‘Error’?

Some parks seem not designed for lingering peacefully among trees, but rather to stand before them in silent reverence. Uğur Tanyeli described such parks as spaces not meant to be lived in, but to be revered — where every path is exact, every tree aligned, transforming nature into monuments to admire from afar. This is most evident in French formal gardens like those at Versailles, where order and symmetry reign supreme, nature tamed and confined. Yet, not all landscapes seek this control. At Antwerp’s Falconplein, trees lean at angles, embracing irregularity and the winds themselves, offering a quieter, more human whisper instead of a commanding presence. After visiting such places, it’s easier to breathe where nature still allows a touch of wildness.

Vaux-le-Vicomte,

image adapted from Gaia Ferro Forgiato, ‘The French Formal Garden,’ gaiaferroforgiato.it/en/the-french-formal-garden/.

It is as if some parks were never meant for spending long, idle hours among the trees, but for standing before them in a kind of silent salute.

I remember reading this idea in a book by Uğur Tanyeli, who described parks designed not to be lived in but to be revered. In these places, the grass does not wait for footsteps (as someone commented in one of my previous posts); every path is precisely defined, every trunk aligned as if at attention, a landscape tamed by the order. At some point, I hesitate to call them nature at all. Such parks transform nature into monuments, spaces not to be entered but rather to be admired from a distance, like relics behind glass.

The Gardens of Versailles,

image adapted from Gaia Ferro Forgiato, ‘The French Formal Garden,’ gaiaferroforgiato.it/en/the-french-formal-garden/.

You can feel this most strongly when wandering parks shaped in the tradition of the French formal garden, like those around the palaces of Versailles. The French formal Garden, ‘jardin à la française’, emerged as an expression of human control over wilderness: symmetry and axis are commanding, trees and hedges arranged in grids, water confined within rectilinear pools.

A friend recently showed me an aerial photograph of the gardens around a historic castle. Seen from above (we would call this bird's-eye view at the school) the composition revealed the order, with almost mathematical coldness. Hedges placed in perfect alignment, trees waiting in ranks, a water feature disciplined into a clean rectangle, and walking paths enclosing it all in a perfect symmetry. As you now know, this was another garden in the French Formal Garden style.

“Beautiful, isn’t it?” he said. I found myself nodding in polite agreement, unsure whether even my best Dutch could express my disagreement. While privately thinking: yes, it is beautiful, but not the beauty of nature. It is a beauty already finished, complete, a beauty that offers nothing more, one you can neither participate in nor converse with. There is no chance to imagine what might be beyond the next turn.

Perhaps the true wildness of nature is an error to be corrected, tamed and shaped by a human being until every element obeys.

Falconplein,

image adapted from www.vdberk.be.

Yet, not every landscape pursues such control. A few blocks north of Antwerp’s historic center, on Falconplein, a square where the trees refuse to stand upright. Instead, they lean at angles, each trunk bending. One might assume a storm passed through, but the reality is different. I learned the truth from another architect, at the time we were passing there for a site visit. The trees were planted leaning to emphasize the prevailing winds from the Scheldt (famous river of Antwerp).

Falconplein,

image adapted from www.vdberk.be.

What I find compelling here is not just the nod to the river’s presence, but the choice to embrace irregularity. Here, the so-called ‘error’ becomes the design. Of course, there is still a human imprint, the initial tilt of the trunks, but compared to the gardens of Versailles, here the interference registers as a whisper, not a command.

Since you now also know what the French formal garden style is, next time you visit a park like this you can experience it for yourself and share your thoughts with me.

And, apart from everything else, how can one really feel at ease after watching the Harry Potter scenes set in a hedge labyrinth? That dark atmosphere, that quiet unease… Perhaps this is, in the end, the very reason for my own discomfort in these parks. Which is why, after leaving such gardens, I find myself breathing more easily in places like Falconplein, where the trees lean and not everything stands in perfect line.

A Tribute to Friends’ Garden

In our society, gardens are somehow merely related to idleness and uselessness which pose a challenge to the conventional notions of what makes life meaningful. These communal spaces embody the true essence of gardens, fostering joy, contemplation, and a sense of community.

And more importantly, the true essence of a garden - which I found in my friends’ garden - stands as a reminder of what truly matters. The true essence of a garden reveals itself not in its productivity and profit; but in the joy of creation and the emotions it inspires.

The Little Garden of Paradise, by the Master of the Upper Rhine, c1410-20

We were having drinks with friends on their lovely rooftop apartment in Brussels. Nestled atop a six-story, aged building, this small one-bedroom apartment had a beautiful roof terrace overlooking the roofscape of three to four-story buildings and their back gardens filled with greenery. As we sat there, our conversation turned to their intention of crafting a wooden structure for planting on this peaceful terrace. With fervent enthusiasm, they spoke of cutting and joining planks, their excitement palpable, as they envisioned their personal space in which new daily rituals can be formed. My friends’ dedication to this small garden, and their focus on cultivating plants in a confined space, highlights the personal significance of gardening even in urban environments. In this way, their garden can be viewed as an extension of their home, an outside enclosure.

An 18th-century miniature of women at their ease in the grounds of the Palace of Sadabad, on the Golden Horn

Interestingly, a garden has always been conceived as a bound space that is secluded from its surroundings. In this sense, my friends’ terrace transforms into a personal sanctuary, a modern embodiment of this old enclosure. The term “garden” itself traces back to the Old English term “geard”, which meant fence, enclosure. Early communities did more than simply build homes; they began to define their own territory, taming nature, erecting boundaries, and creating enclosed spaces. The garden, thus, intersects with one of humanity’s most important endeavors; the domestication of nature and the establishment of social order. Once a space strictly for cultivation, it has grown to symbolize power. No longer just a practical space, the garden evolved into a realm of the elite class (The Gardens of the Villa d'Este in Tivoli, Italy), of kings (The Gardens of Alhambra in Granada, Spain), and even of gods. I remember visiting the Majorelle Garden in Marrakech, Morocco; a botanical garden created by French painter Jacques Majorelle in the 1920s and 1930s. Following his death, this garden was owned and restored by fashion designers Yves Saint-Laurent and Pierre Berge. The garden is renowned for its vibrant cobalt blue color and its extensive collection of exotic plants. I had a chance to visit this oasis after I waited in line, as a patient and eager tourist. Upon entering, I was greeted by beautiful medium-sized trees, cacti, and exotic plants all in varying shades of green. The famous Yves blue revealed itself almost immediately with a glimpse of a striking contrast against this green background. I spent my time wandering around the garden, feeling insignificant and unfamiliar amidst the exotic flora as if the world had been stripped of color, leaving only the deep greens, bright yellows and Yves blues to captivate my senses.

Majorelle can be seen as a long-fought battlefield where victory is signified by the collection of exotic plants. It stands as a testament to the creator's power over nature, a potent symbol of the domestication of land. This garden, a deliberate creation, radically opposes the surrounding reality. It is a paradise on earth, meticulously crafted by the elite class, embodying the power and beauty of human desire.

The Majorelle Garden and my friends’ terrace garden represent two opposite ends of the gardening spectrum. The Majorelle Garden is grand, and renowned, a symbol of power and artistic expression. In contrast, my friends’ terrace garden is modest and personal. However, there is a fundamental essence that unites both gardens: the human desire to create, cultivate, and find a place to contemplate in nature.

Gardening invites us to reconsider its role within modern urbanization. Can gardening, an important architectural archetype, blur the lines between being a place for contemplation and mere foraging or intensive farming? A garden can host production but it is not confined solely to a productive space. It is a projection of life ambitions encompassing pleasure, meditation, debate, love, art, and friendship—facets of human experience often undervalued today. Because in modern cities, the economy rules our lives and dominates our existence. Considering the architectural norms in Belgium, the requirement of a 4-5 m² outer space (terrace, balcony, garden) and an additional 2-3 m² for each sleeping room in all new buildings may not entirely resolve the issue, but it will certainly enhance the quality of life. Having said these, I am actually quite happy to encounter communal gardens in my daily life. While addressing this challenge on an individual basis may be complex, approaching it as a communal concern and creating shared gardens in parts of streets or on rooftops presents an admirable solution.

Communal garden, Ghent

In our society, gardens are somehow merely related to idleness and uselessness which pose a challenge to the conventional notions of what makes life meaningful. These communal spaces embody the true essence of gardens, fostering joy, contemplation, and a sense of community. And more importantly, the true essence of a garden - which I found in my friends’ garden - stands as a reminder of what truly matters. The true essence of a garden reveals itself not in its productivity and profit; but in the joy of creation and the emotions it inspires.

Iron Tie Rods

For structural stability, old structures' masonry walls are fastened with iron tie rods. Because, despite the load-bearing nature of the facade in these structures, it lacks a robust structural connection with the rest of the building, which can lead to failure of these walls. A peculiar challenge often found in these old buildings lies in the arrangement of floor and roof joists that run parallel to the front and rear facades, interconnecting with party walls shared between buildings.

Ghent - leaning buildings

Moving to another country or even another city make it challenging to define the particular space that feels like home, considering that home often refers to a personal and spatial haven for everyone. This situation rather becomes an in-betweenness where you are not sure what home really is. Going back to Ankara makes my room there feel like a museum of memories, each corner a collection of the past. And, returning to my apartment in Antwerp, though familiar, still doesn’t give me that sense of home. Actually I feel a bit like a turtle, carrying my home on my back, wandering through the realms of uncertainty.

I’ve been living in Belgium for 5 years and I have changed 2 cities and lived in 5 different apartments. Along this journey, I’ve met many people—some evolving into friendships, and others remaining acquaintances. Now I will be moving to another city and yet another apartment. But this time it is not really moving to a new city because I’m going back to the city where it all began, Ghent.

Now, in pondering the concept of home and relocating once again, I want to convey a short sentiment about discovering peace and reassurance in the familiar sights, before delving into the topic of iron tie rods.

During my time in both Ghent and Antwerp, I noticed something interesting in both cities — buildings leaning and bulging outwards! Some old buildings in both places have this interesting feature where they seem to bulge outwards. Walking on narrow streets surrounded by these bulging and leaning buildings takes me back to those times when we visited my father’s childhood neighborhood in Mamak, Ankara where my grandparents and aunts lived when I was a child. It was a single storey house in a neighborhood with many other single storey houses. The house had a huge garden with huge trees (or everything seemed huge to me back then). The streets were narrow and winding, weaving through structures with irregular walls that defined and followed these paths.

Antwerp - buildings leaning and bulging outwards

So, whenever I stroll through the streets adorned with buildings leaning and bulging outwards, such as the ones in Ghent and Antwerp, they remind me of those streets from my childhood. And I find peace in the familiar presence of these structures. I envision these leaning structures of Antwerp and Ghent as silent observers, their bulging parts akin to bellies, keenly watching over the surroundings and embracing the street. Similar to how a belly may struggle to fit comfortably in a shirt, these buildings, too, seem to require a set of proper buttons to complete their distinctive appearance. And these buttons are iron tie rods or so called wall washers.

In many cities in Europe, you'll often encounter iron tie rods on old masonry buildings. While you might associate them with Ezio using them to climb buildings in Assassin's Creed, the reality is quite different.

For structural stability, old structures' masonry walls are fastened with iron tie rods. Because, despite the load-bearing nature of the facade in these structures, it lacks a robust structural connection with the rest of the building, which can lead to failure of these walls. A peculiar challenge often found in these old buildings lies in the arrangement of floor and roof joists that run parallel to the front and rear facades, interconnecting with party walls shared between buildings. This spatial arrangement creates a structural vulnerability due to inadequate lateral restraint to limit the sideways movement. In today's building methods, walls are kept steady by using the floors and roofs to hold onto them which provides lateral restraint. However, the front and back walls of these buildings are only connected at the roof and edges, leaving the facade walls without lateral restraint. Over time, these masonry walls can push out and bulge outwards, posing a risk of collapse. To mitigate this risk and stabilize the walls, iron tie rods are used. They can be found in a range of sizes and forms. They also become a part of the facade's ornamentation.

When I deal with a project involving iron tie rods, initial impressions often provide more clues than concrete facts. It is difficult for me to determine if the iron tie rods were added during the initial construction or if they were placed later. And the presence of iron tie rods may suggest that the building has faced structural challenges. Based on my observations of buildings in Ghent and Antwerp, I often see a correlation between the position of iron tie rods and the internal floor heights. However, making definitive assumptions about internal floor heights relying solely on external clues of iron tie rods is not always reliable.

Therefore, it's important to bear in mind that the absence of tie rods doesn't necessarily imply the absence of structural concerns, and their presence doesn't automatically indicate poor construction. These iron tie rods are like buttons on the shirt of structural stability.

Dear Rainwater

In a small country like Belgium, dry land is needed more than wet. In order to have more dry land, they reshaped their landscape and oriented water through canals. These new dry lands have become built-up areas. And these built-up areas turned this small country into a densely populated one. As a result, the soil’s existing ability to retain and infiltrate water is lost.

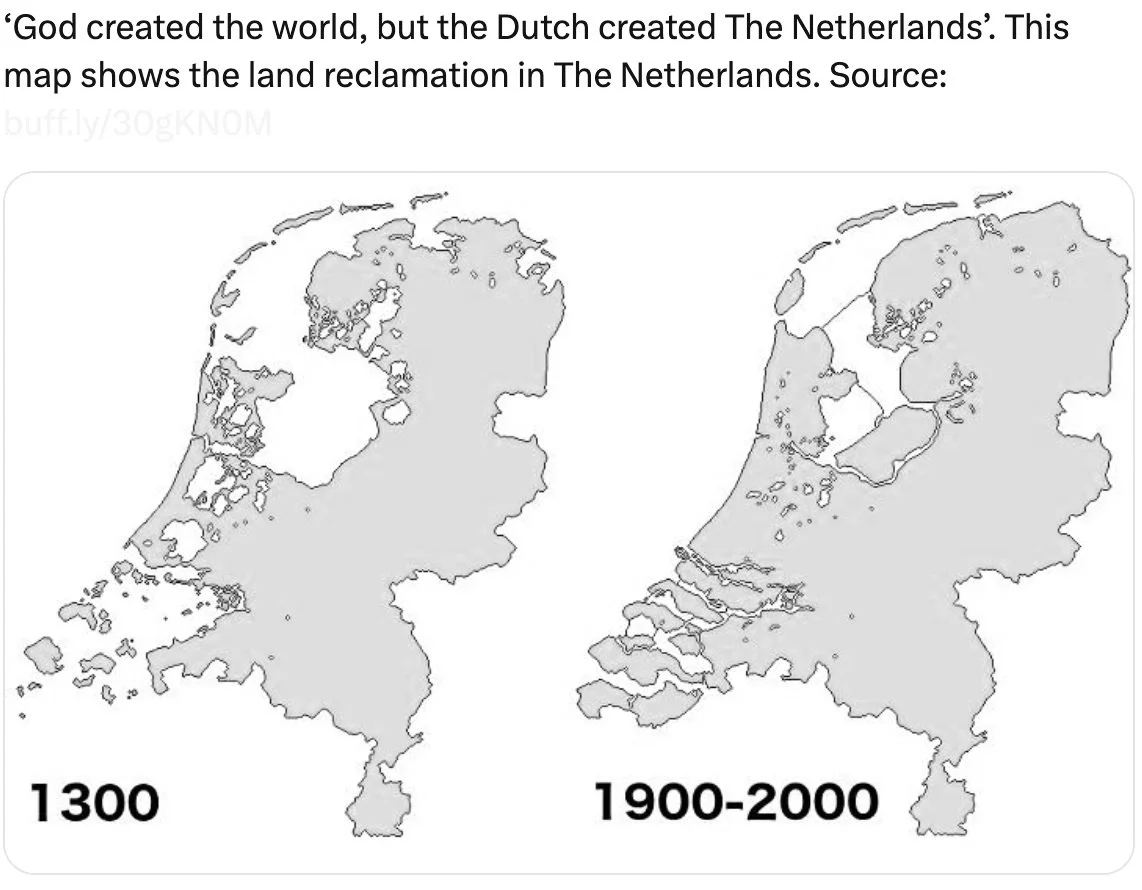

source: twitter

Last week was a chaotic week at the office due to the new ‘rainwater regulations’ and I remembered this image my brother sent me a few years ago. It shows a comparison of land reclamation between the 13th and 20th centuries in the Netherlands. While there are some comments about the fault information on these maps, I want to focus more on the case of Belgium and the dewatering reality in this type of countries.

I don't think you would believe it if I told you that there is a water shortage in Belgium. But this is true. In the list of countries with water shortages, Belgium ranks 23rd between Andorra and Morocco. If it has rained a lot, that doesn't mean there is enough water. You need to be able to hold the rainwater and create enough time for it to infiltrate the groundwater.

In a small country like Belgium, dry land is needed more than wet. In order to have more dry land, they reshaped their landscape and oriented water through canals. These new dry lands have become built-up areas. And these built-up areas turned this small country into a densely populated one. As a result, the soil’s existing ability to retain and infiltrate water is lost.

Additionally, oriented water through canals drains into rivers or seas, preventing water retention and infiltration. Rainwater needs sufficient time and space to infiltrate groundwater. This resulted in a significant drop in groundwater which is the main source of water for plants and our drinking water.

If you pave everywhere or make canals to orient rainwater, there is not enough time and space left for that water to infiltrate through the soil. When it rains really hard, the water has to find its way somehow. That's how we usually get floods in our cities. Because there is not enough time and space for water to infiltrate.

In new buildings or renovations in Belgium, collecting as much rainwater as possible from roofs and reusing it for households or maintenance was already very important. In certain cases, you also had to place infiltration crates to provide slow infiltration through the back gardens. As of this week, this has changed dramatically and become more stricter. (I completely agree with the decision and like it very much.) But explaining this to customers is quite difficult. For most, it just means additional cost. As a result, last week some people had to carry the burden and submit the projects before the new rainwater regulation. And I was one of those people...

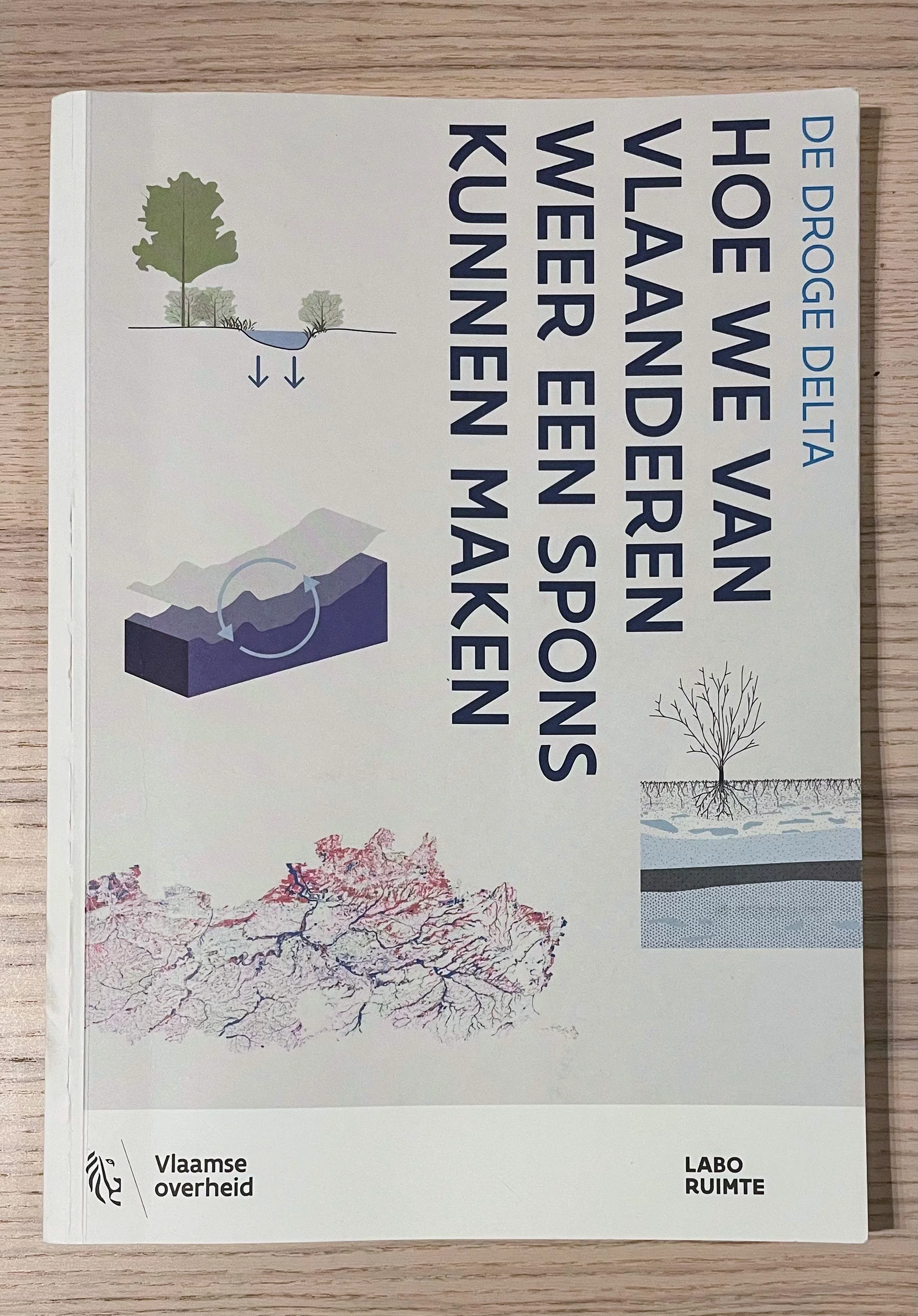

De Droge Delta. Hoe we van Vlaanderen weer een spons kunnen maken - LABO RUIMTE, Vlaamse Overheid

One of the best publications I have read lately. My text is largely inspired by this publication because the introduction of the new rainwater regulation coincided with my reading of this publication. And I took the statistic figure I used in my text from this publication. It also contains nice graps and photos. Still, it would have been nice to have more explanations below them.

Goodbye (sort of)..

What defines buildings as unbuildable? I have been working as an architect for a few years now and lately I have often asked myself this question. What defines buildings as unbuildable?

B I D Y B F K C G B D A

UNBUILDABLE

What defines buildings as unbuildable? I have been working as an architect for a few years now and lately I have often asked myself this question. What defines buildings as unbuildable?

What stops me from designing a curved brick wall instead of a straight wall with a regular masonry? Why do we usually opt for ‘wildverband’ instead of thinking in detail about the placement of facing bricks? Working in a professional life comes with some burdens, such as getting away from the so-called free academic environment and structuring everything through the lens of buildability and profitability. A tension between losing the ability to imagine in working life and failing to grasp the realities of the professional world throughout academic training followed by the notion of unbuildable. The absence of any mediation between these two ends of the tension affirms their mutual ignorance. But still, what defines buildings as unbuildable? Is it mere profitability? Or is it the technology behind the whole design which underlies the possibility of building a structure? Maybe it is our imagination that is formed during our architectural education? Or perhaps the quality of the project decides and makes the building unbuildable?

Notion of unbuildable, in my opinion, is about the gap between the professional life and the academic part of architecture. When this gap widens, we talk about unbuildable; when this gap narrows and the two overlap, the notion of unbuildable is lost. This is an understanding of where designing and building is neither mere profitability nor intensive theoretical research, but something in between. When a person reaches this state of in-betweenness, they can answer this question. In order to explain this state, I'll take a stance from my current perspective, from my work life. I did not follow my interest in academic studies, choosing instead to become a working architect. Being situated in the professional life and working as an architect forms one universe. This is Mars. Then there is also another universe where the academic life of architecture takes place. This is Venus. Professional life of architecture is from Mars and the academic one is from Venus.1 And I named their (imaginative) overlapping condition as the FRINGE. I have been trying to put myself exactly where this overlap is. As a result, the act of writing and working as an architect in professional life forms a new condition that overlaps these two universes. FRINGE can be defined as this blurring condition where the interaction with architecture is neither mere pragmatic nor intensive research, but something in between.

FRINGE AND GOODBYE

Another place where the FRINGE emerges as an important mediator is the transition from academic life to professional life or vice versa. The act of transition and redefinition of self complicates the process, removes any sense of adaptation and highlights the importance of the FRINGE as a mediator. FRINGE is not a passive act instead it requires your time and your dime. Finding your own FRINGE and then being able to make necessary time and space to reflect on architecture is not easy and this difficulty can ‘further’ encourage someone to quit architecture.

Here another question pops up. What makes someone quit architecture and can FRINGE help someone stay in architecture? Even though there is more diversity in the field of architecture, it is still exclusionary. Professional life demands long hours of work that disrupt work-life balance. Architectural education costs a lot of money. In the end, you spend more time than the time you spend on your architectural education just to earn the money you invest in your education. All these and more are the part of something much larger. Still, FRINGE can encourage us to stay in architecture during our early academic or professional lives. Perhaps it won’t be enough, but it is still something to begin.

I found my FRINGE in writing. It enriches my knowledge and encourages me throughout my professional life. At this moment I can only say that I hope you will also find your FRINGE!

In the beginning of this piece, I have put some letters that you may see as accidental. Those are the initial letters of some people that I know who quit architecture. Just some of them… I wanted to take this moment to express my deep appreciation for all their invaluable effort and guidance throughout the physical and emotional stress of architectural education and professional life. You all are already missed.

This is my humble goodbye to you

Goodbye Friends

Goodbye (sort of)...

Notes:

1. I borrowed this naming from a book. Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus (1992) by John Gray

Kind of a Memoir

I am in grief and I don’t know where to put all the pieces of myself. I was deeply saddened over the past weeks by the earthquake in Turkey and I still am. I have been trying to gather my thoughts on this and I still can’t find the right words to express myself. I am sad and angry.

I am in grief and I don’t know where to put all the pieces of myself. I was deeply saddened over the past weeks by the earthquake in Turkey and I still am. I have been trying to gather my thoughts on this and I still can’t find the right words to express myself. I am sad and angry.

As we witnessed through the acts of all volunteers and non-governmental organisations in the earthquake zone, collaborative movements are one of the most powerful tools of humans. This collective action also forms the essence of the discipline of architecture. An essence in which the different parties are involved to share their knowledge. Isn’t it the reasoning of all the group works during our architectural education or collaborations in our professional life?

But when it comes to reality, it becomes difficult to pursue this cooperation in architecture. Polarised fields, political conditions and the tendency towards individuality makes it impossible. But it is also certain that the very qualitative studies have been shared. For instance, lately I come across a lot about earthen and wooden structures. However, we should be able to create a workspace that can gather these two different actors and their insights.

I believe that the involvement of different fields should shape cities and this is an inevitable truth. No one can overcome the challenges that our built environment deals with alone. A new workspace with various actors is essential.

Kahvehane | A Dead Metaphor

Architecture is a craftmanship. Relationship between master and apprentice shapes the future of the profession. You need to be curious enough to observe your master.¹ It wouldn’t be comprehensive to reduce the meaning of master to a person. It can mean any inspirations in your life.

At a certain moment in my life, I have realized that walking is the moment that I observe my surrounding. During my walks in Ankara (my hometown), I am always intrigued by ‘Kahvehane (Coffee House)’. If you observe these spaces, you can feel joy but also sadness that are embedded in them. I still remember how people were interacting with each other in Kahvehane. Interaction was emerging as a form of conversation or intense discussion. When I look back now, I can say that my desire to write about this space emerged that day, during those walks in the neighbourhood… I believe, we need to embrace these peculiar moments as architects. Now, I sit back and try to grasp that moment and that curiosity, which have led me to envisage Kahvehane disconnected from its roots.

Architecture is a craftmanship. Relationship between master and apprentice shapes the future of the profession. You need to be curious enough to observe your master.¹ It wouldn’t be comprehensive to reduce the meaning of master to a person. It can mean any inspirations in your life.

At a certain moment in my life, I have realized that walking is the moment that I observe my surrounding. During my walks in Ankara (my hometown), I am always intrigued by ‘Kahvehane (Coffee House)’. If you observe these spaces, you can feel joy but also sadness that are embedded in them. I still remember how people were interacting with each other in Kahvehane. Interaction was emerging as a form of conversation or intense discussion. When I look back now, I can say that my desire to write about this space emerged that day, during those walks in the neighbourhood… I believe, we need to embrace these peculiar moments as architects. Now, I sit back and try to grasp that moment and that curiosity, which have led me to envisage Kahvehane disconnected from its roots.

We, as humans, have been challenging the cities we live in. Cities are in a state of uncertainty. We should be aware of the entropy of any creation. Our memories and pasts are disappearing. Today, we can easily witness how these processes can take place so suddenly. However, they sometimes happen in a natural rhythm that they disappear unnoticed. In my opinion, Kahvehane was one of those spaces that was lost with the lapse of time.

Diversity has been an important value of democratic society and civic space. Before, you could encounter any people regardless of occupation, social status or political outlook in Kahvehane. However, women were always excluded at that time due to the separation between social spheres. Publicness, political sociability and conversations and debates about the broad range of topics, led Kahvehane’s restrictions and closedown in the history.² Kahvehane culture formed and spread the viewpoints of ordinary citizens while provoking an outpouring of public opinion. Democracy understanding of urban life was shaping around Kahvehane. Civic definition of this space was established throughout the Ottoman Empire and it was expanded over Europe in 17-18th century.³ Various subjecs were discussed in Kahvehane and for instance one of them was literary works. A weekly bulletin emerged in a coffee house opened by playwright Josep Addison. Later, this bulletin became a newspaper which is still called “The Guardian”.⁴

In the present day; civic quality, democratic hope, public sociability and alternative political existence of Kahvehane are not exist anymore. Today, Kahvehane is only associated with retired or unemployed people. In fact we could even argue that Kahvehane is not exist anymore and it is shaped as a cafe that excludes certain group of people.

Kahvehane is a dead metaphor now.

Additionally, the idea of democracy has shifted from physical to virtual. The print and digital media are representative for today’s democracy. We do not seek for public space, debating chamber, Agora or Pnyx anymore.⁵ Perhaps we could further argue that the print and digital media have supported the birth of undemocratic architecture which have promoted virtual existence.⁶

My intention, or perhaps I should call it my hope, is starting a discussion from this situation. How can we re-establish a democratic network in the city while unlocking the potential of Kahvehane as a civic space? How can we recast a space for democratic purposes?

Kahvehane, similar to cafes, is located on the ground floor where you have your physical and visual connection with the street. Nowadays, in contrast to this connection one can experience the closed box front extensions of these spaces. These privatized boxes create boundaries with a limited visual connection on the ground floors of built environment. This opposes with the civic and democratic quality of the space.

However, I have encountered two other types of Kahvehane spaces; one with a defined terrace in the front and another one with an undefined pocket in front of the entrance door. Most interesting feature of these front spaces is being an in-between. It is a space where one could keep in touch with both urban life and the conversation in Kahvehane. It creates a thoughtful gap to prepare the person for a conversation and to observe the differences in the surrounding. Hence, the space defy the boundary.

History understanding of today’s politics has been based on copying without grasping the essence. This also reduces the meaning of the history. Here, we should learn from the historic roots of this space to be able to respond to the current democratic tendencies of the citizens. I believe, all the pre-assumed definitions of gender, social status, political outlook and cultural belonging should be left aside to achieve a sustained attention on any subjects in Kahvehane. It should be a place where one becomes accustomed to differences in the city.

With the questions that I have asked, I have pursued my observations as a response to my curiosity. If there is an architectural entropy, I have used my architectural tools to increase this entropy further.

I think, architecture cannot create democracy on its own. Democracy rests in the hands of people. However, I have a belief that architecture can become a part of the political, social and cultural struggle for a better world.

Notes:

1. If you check the website of Le Corbusier Foundation, you can see the list of refused interns. In the list from 1949, we can also see Turgut Cansever. I think we can easily argue that T. Cansever wanted to observe his master (his inspirition) at that time, considering some similarities between his and Le Corbusier’s architectural approach.

See. http://www.fondationlecorbusier.fr/corbuweb/zcomp/pages/AtelAtel.htm

2. Yaşar, Ahmet. Osmanlı’da Kamu Mekanı Üzerinde Mücadele: Kahvehane Yasaklamaları, Uluslararası XV. Türk Tarih Kongresi, Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları, 2006.

3. McDonald, Hollie, Social Politics of Seventeenth Century London Coffee Houses: An Exploration of Class and Gender, 2013.

4. Brian Cowan, What Was Masculine About the Public Sphere? Gender and the Coffeehouse Milieu in post-Restoration England, History Workshop Journal, Volume 51, Issue 1, 2001.

5. In ancient Greece, Agora was the town square and the Pnyx was an ampitheatre where citizens debate. For further reading in this context, I recommend The Spaces of Democracy by Richard Sennett.

6. For an interesting further reading in this context, I recommend the chapter “Ceci tuera cela (This will kill that)” of Notre-Dame de Paris by Victor Hugo.

Awakening of the Public Stage

I believe that architecture is a loop. In the practise of architecture, one may find him/herself at the point that he/she started. By going through this process, one may prove the existince of the loop to him/herself.

Every starting point is a final point.

Or every final point is a new starting point.

Loop creates opportunities as well. Every new point that we define during our architectural process might be a beginning of another loop. Obviously, it would not be a comprehensive approach to restrict architecture to this simple state of linked loops rather we should embrace the productivity and the potentiality that the loop creates.

I believe that architecture is a loop. In the practise of architecture, one may find him/herself at the point that he/she started. By going through this process, one may prove the existince of the loop to him/herself.

Every starting point is a final point.

Or every final point is a new starting point.

Loop creates opportunities as well. Every new point that we define during our architectural process might be a beginning of another loop. Obviously, it would not be a comprehensive approach to restrict architecture to this simple state of linked loops rather we should embrace the productivity and the potentiality that the loop creates.

Some weeks ago, my friend Bartek was talking about a ‘new’ public spaces that are formed in the cities. Balconies..

I was both intrigued and surprised when I heard the phrase of ‘new public spaces’. Discovery of public spaces, wouldn’t it be inspiring? I was surprised as well because we are living in an age where the foundations of how people interact is displaced and the notion of public is increasingly privatized.¹

When did the modern balcony appear? It showed itself in early 19th century Paris. After Hausmann’s renovation plan of Paris, balconies were important observation points for bourgeois.² Balcony has been an undefined space which is mostly associated with the temporary uses. In Venice the balcony was a place for urban gossip³, in Tel-Aviv it was a space to provide openness and ventilation⁴. Sometimes the balcony was used to store, sometimes to contemplate or to rest. Throughout history, we have seen the balcony as an urban artefact which represents cultural and social values of its region.

Balcony is a liminal space between private life of home and the public sphere of the city. It constitutes a fundamental act of bringing people together. Public space aims to reduce physical distance between individuals, however; the balcony explores the opposite situation. Although you can spectate the people on the street, it is difficult to hold a conversation or to be involved in the event. The distance and the social encounter patterns that are created by the balcony, challenge us to define this place as a public space.

Since the epidemic of COVID-19 outbreak, we are going through hard times and abrupt changes in the social patterns. The balcony is brought back to life by the people during this upheaval. Collective act of hope and solidarity are being represented on balconies. People who are giving concerts, applauding health workers and holding conversations with the people on other balconies are the middle of social interaction now. They become both the spectator and the subject. The balcony is not only a liminal space anymore, It is a ‘new public stage.’

Today we are at that unique moment. The beginning of another architectural loop that might create another journey or that might end up at the very point we started. And I am looking forward to see this process. Can the balcony become more than a public stage? Can we see the political autonomy which should be existed in public spaces, on balconies as well?

I don’t know yet. What I know for now is, I am looking forward to move a house with a nice and small balcony in the future…

Notes:

1. For further reading in this context, I recommend Yıkarak Yapmak by Uğur Tanyeli or only the chapter 14 in this book.

2. Bell, Duncan, and Bernardo Zacka. Political Theory and Architecture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

3. Foxhall, Lin, and Gabriele Neher. Gender and the City before Modernity. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

4. Aronis, Carolin. The Balconies of Tel-Aviv: Cultural History and Urban Politics. Israel Studies14, no. 3 (2009): 157-80.

Architectural Artefact of Inquiry

Phase I _ Awareness

I have realised that architecture has become easily consumable.

Humanity has made enormous developments. As we progress into a technological century, we are confronted with the repercussions. Through dissemination of architectural knowledge and with social media, architecture has become easily consumable. Our ability to consume and digest new architecture has changed the components of inquiry process as well as space and time intimacy. The reduction in the time frame of procurement, resulted in increased gap between thinking process and architecture.

Phase I _ Awareness

I have realised that architecture has become easily consumable.

Humanity has made enormous developments. As we progress into a technological century, we are confronted with the repercussions. Through dissemination of architectural knowledge and with social media, architecture has become easily consumable. Our ability to consume and digest new architecture has changed the components of inquiry process as well as space and time intimacy. The reduction in the time frame of procurement, resulted in increased gap between thinking process and architecture.

Phase II _ Dislocation

I have been struggling to reclaim architectural thinking process.

How can the consumption process relate with the idea of ‘architectural artefact of inquiry’? Dislocation was the spark that makes me think about the tension between artefact and consumption. Drawings and models act as the artefacts in being reflective of the architects’ detailed study of precedents, and blended knowledge of contemporary and historic. Thinking process of today’s architecture is disrupted by architectural artefacts which are remarkable and unusual. They tell stories with their lines, planes and points.

Phase II makes them stop, makes them think and makes them question.